Why it’s not about Fundamentals: Moving on From Outdated Coaching Styles

“I love your ideas but I’m not sure they can be applied in any given situation. I’m coaching a young team and most of them don’t have the skills to implement your kind of drills. I just saw the post about shooting where you explain how one hand form shooting is useless and players should train on real game situations. While I would tend to agree, how can I train shooting when a player can’t even shoot or uses two hands? What would you do then? Once a player is mature fundamental-wise, I think decisions can be implemented to simulate a real game. However, if skills are missing, I’m not sure it would be of any help. You can’t ask someone who can’t walk to run a marathon right?”

It is great to see coaches all over the world engaging with the Transforming approach. This was a message we received recently from a coach working with youth players. To unpack this question, it is necessary to begin by considering what fundamentals even are? Are there really optimal movements and techniques that can be drilled in closed environments and then brought out at the right time in the game? Is there even such a thing as a specific technique that works exactly as practiced in different situations?

The key concept that we cannot shy away from is that fundamentals rarely appear as they have been practiced. The game itself consists of players solving problems that are presented to them in a unique manner every time. In the example of form shooting, do players ever shoot in the game even close to how shooting is practiced within form shooting drills? Do players pass similarly to line passing drills, finish as practiced in 1-on-0 etc… We commonly believe that players must have rehearsed and ‘mastered’ a movement solution/ technique before ‘using’ it in the game. This belief is incompatible with the nature of how humans move and interact with their environment in any domain within life. Many of the fundamentals that have been taught over the decades actually contradict the most effective self-organisational movement tendencies inherent to every athlete.

Thinking deeply about this topic is a tricky one to come to grips with. Society as a whole and entire upbringings and careers in basketball (for players and coaches alike) are built on the premise that there are ‘fundamental’ techniques. Entire coaching educational programs and the careers of famous coaches have been built on this belief. Many believe that fundamentals have to be first taught explicitly in highly controlled environments in order for players to succeed. Indeed, this is supposedly the hallmark of a ‘good’ coach in environments all over the world. Therefore, moving away from this linearised approach is challenging when such entrenched socio-cultural-historical constraints exist. However, embracing the alternative becomes easier when understanding that there is compelling research suggesting that the opposite approach is more effective. Players can develop techniques more effectively in-context of the game, while navigating a more complex and chaotic environment than the ones seen in many traditional basketball practices. The next focus of this article will be sharing how this can be achieved, specifically with beginners.

When embracing a nonlinear pedagogy, players may come to their own movement solutions because every player is different: there is no such thing as a ‘one size fits all’ approach (Chow et al., 2021). This is why understanding an ecological dynamics framework is essential. When considering how humans move to achieve any goal-orientated task, it quickly becomes apparent that there can be no such thing as a fundamental skill. Players all move differently because every player is so inherently different. What is fundamental for one player may make no sense to another. For the many coaches who believe in fundamentals, they often have ‘bundles of beliefs’ as opposed to a guiding theory informed by the science of human movement. This was the topic of an excellent recent podcast episode between Stuart Armstrong and Phil Kearney on the Talent Equation.

If coaches believe that training techniques in isolation is conducive for skilled performance, then we have to reconsider what skilful performance is. Is it about being robotic by repeating pre-drilled techniques, or about being adaptive based on what solution solves the problem for one specific moment in-time? This indicates how movement within basketball may be better thought of as a problem-solving activity (Myszka, Yearby & Davids, 2023). This naturally leads into a consideration of what environment prepares players to be more adaptive from the very start. Does practicing to avoid errors really help a player become more skilful, or instead, is it about appreciating how errors are part of the process as players figure out what is and is not functional within their movement solutions?

Naturally, we now have to consider how we can create environments that are more suited for beginners. As Davids et al., highlighted in their seminal 1994 paper, there is a level of “muscular-skeletal anarchy” which is evident in novices as they start playing basketball (Davids et al., 1994). However, the key to such players becoming more skilful lies in exploration as opposed to rigid instruction. Can beginners explore as much as possible, as early as possible as opposed to being confined into highly specific positions? What if such players could move even more creatively if they were given time to solve the problem and move in their own ways? As Stuart Armstrong has said on the same subject, many coaches are well-intentioned and think that teaching techniques provide a shortcut, but it actually hinders the process in the long-term.

DOWNLOAD OUR PLAYER DEVELOPMENT SSGs BOOK

In order to embrace a nonlinear pedagogy with beginners, it is absolutely not a case of merely rolling the balls out and playing 5-on-5 in practice. This is not beneficial as there won’t be enough opportunities for action (affordances) for players to become skilful and develop functional perception-action couplings within the practice. At the same time, it’s not about just playing generic small-sided games such as 2-on-2, 3-on-3 etc. Specific learning environments need to be created which allow players to become more skilled at what is most important for their current ability level. With beginners, this may lead to a focus in a few key areas:

- Recognising and converting an offensive advantage

- Finishing off drives against a primary and/or help defender

- Creating an advantage off the dribble through 1-on-1

- Shooting

In the example of shooting, at Transforming we would refrain from teaching specific positions to players. Instead, we would provide an external focus of attention with the intent to score BRADs (Back Rim and Down). This encourages players to self-organise into strategies which release the ball with optimal arc in order to increase the odds of scoring a BRAD. With beginners, this could be achieved through several large advantage 1-on-1’s, which could be as simple as a defender passing the ball to the shooter and closing out at a fairly long distance, but always coming from a different angle and location. The shooter may receive three points for a BRAD, and one point for any other make. This 1-on-1 could then be changed in a variety of ways. Differential learning could supplement this by helping beginners explore different ways to shoot and become familiar with their body: e.g. shoot out of different stances, land in different directions, constantly change range and location etc. Differential learning serves as a great alternative to form shooting in this instance. As recently asked, what happens if a player shoots with two hands? The coach could simply cue the athlete to “find a solution to shoot with one hand.” This does not mean the beginner is being confined by highly specific positions, as there are a variety of ways they could solve the problem while using one hand to shoot.

Within small-sided games tailored for the beginner, coaches must think creatively to ensure the level of challenge is just right. If a 1-on-1 is too difficult, then maybe the defender can only play defense in the smile (charge circle). If players still struggle, maybe the defender cannot jump. This still guarantees a level of realistic information remains, without depriving players of the information they need to attune to within the game. If a 3-on-3 is too difficult, then maybe one defender has to play defense with their hands behind their back. There are an abundance of different ways in which tasks can be simplified rather than having to revert to on-air practice and technique instruction. This is a fun process as it requires becoming far more creative as a coach by seeing what the players struggle with, and then thinking of a new task constraint to simplify that problem. This is very different to working off a checklist of drills and techniques that must be taught.

Even when it comes to the dominant approach to coaching and the commonplace practice of teaching moves and techniques, there is no empirical evidence that this approach positively transfers. Coaches cannot prove to successful players who trained with fundamentals as proof ‘it works’, because we simply would never know what else they could have been if practicing with contemporary methods. While in many cases a runner would not prepare for a marathon by immediately attempting to run a marathon, going on a treadmill and working on the correct biomechanical positions needed for the race will be even less adequate! As Alan Dunton has said, a swimmer wouldn’t prepare for a 400 metre race by training in a bath tub, but you may be able to photograph an optimal biomechanical technique! This is a great analogy for the concept of form shooting and all the other fundamentals within the basketball world. In closed environments the technique looks great, but in the chaotic environment of the sport itself, a pre-rehearsed fundamental is not even relevant. This is because the opponent dictates what is and is not possible. Therefore, what benefit does repeating ‘optimal’ techniques provide when the techniques that emerge in the game are dictated by the ever-changing environment?

Alan Dunton discussing the notion of “swimming in a bathtub” in E18 of the Transforming Basketball Podcast!

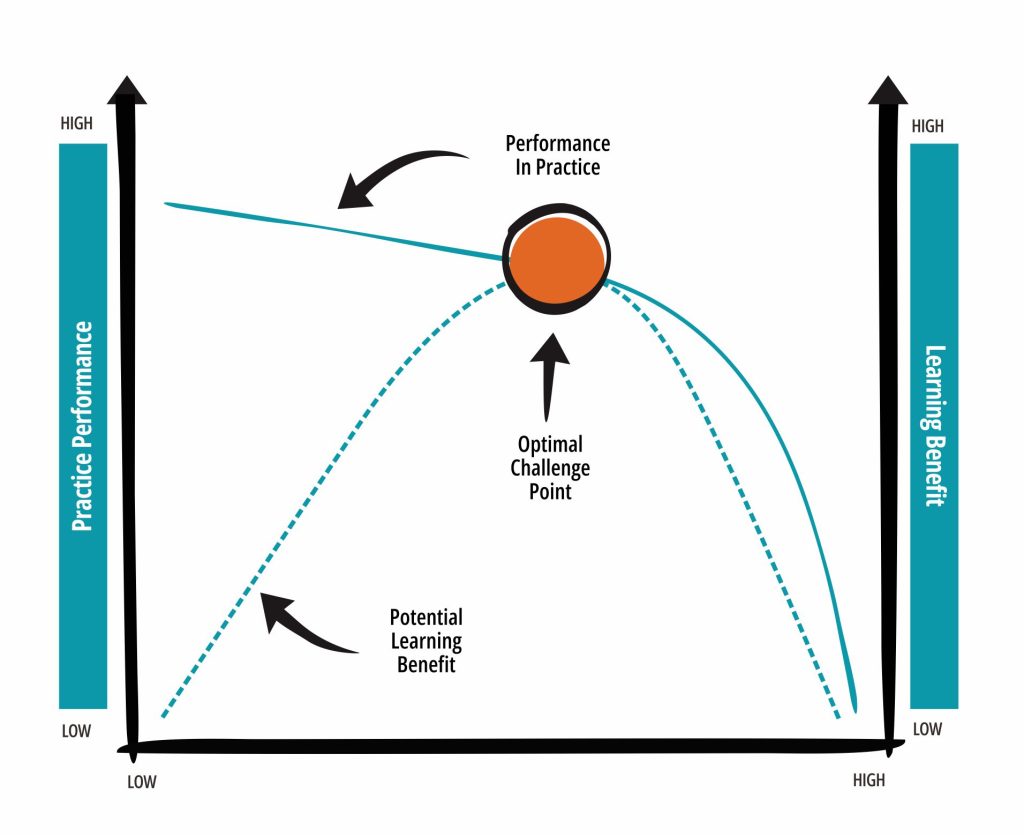

The answer in helping beginners through a contemporary approach lies in scaling the practice activities at a level that is ‘just right’ for the players. This is where Guadagnoli & Lee’s optimal challenge point is a useful framework (Guadagnoli & Lee, 2004) . Despite its roots in information processing theory, it is useful for coaches to consider when designing tasks through a constraints-led approach (CLA). Coaches can create small slices of the game, with constraints designed to ensure that the difficulty level is not too easy but also not too hard. Even a player that has never played basketball before will get stuck in and have lots of fun when confronted by some type of dribble tag game or playing in a big advantage 1-on-1/ 2-on-1.

With the attitude of fundamentals first, complexity later, we must also ask the question of how we would even know when the players are ready for more advanced concepts? Learning is incredibly nonlinear with players learning over different timescales. Additionally, during the course of a youth basketball season, typically new players will join while some players may be injured or miss practices due to other commitments. When faced by such constraints, it’s simply so much easier to use a constraints-led approach than traditional drills! Additionally as shared throughout the article, impressive fundamentals demonstrated within practice accounts for nothing. This is because there is no guarantee that players exhibiting such techniques are actually effective performers within the game. This is the whole notion of the ‘workout warrior’: the player that looks incredible in practice, but can’t get it done when it comes to game-time. This article explains why this phenomenon is so prevalent throughout the basketball world.

In my experience as a coach developer, for the coaches that have embraced a contemporary approach, this is probably the most common reason as to why coaches moved on from the dominant approach. In other words, they thought deeply about the players they worked with, and realised that the lack of practice to game transfer was compelling enough to serve as a compelling rationale for embracing change.

As coaches we play a critical role not just in developing skilful behaviours, but also ensuring that our players have a positive experience of the sport. This is perhaps most profound at the youth level. With this in-mind, we must ask the question of what approach will youth players enjoy more?

A linear pedagogy involving lots of drilling, correction and teaching of techniques

OR

A nonlinear pedagogy involving small-sided games, purposeful constraint manipulation (the CLA) and opportunities to explore and play for the whole practice

This is obviously a no-brainer! While the research overwhelmingly suggests that a nonlinear pedagogy is far more superior for skill acquisition, many coaches still find this evidence difficult to accept. This is understandable as this suggests that there is a better alternative than the coaching approaches we have used for our entire careers. However, we simply cannot doubt that a nonlinear pedagogy is far more enjoyable for players, contributing to greater athlete satisfaction and retention within the sport of basketball. For 99% of coaches working with youth players who play basketball for fun, enjoyment and social reasons, the question becomes simple: “why would you NOT embrace this?!”

We have to put our ego aside as coaches and be willing to give this a try. Our advice would be this: give it a try for three weeks and avoid teaching any techniques or using drills. Just see what happens… Ask your players what they think and observe how they move and interact within their environment. We guarantee that you will never go back!

Feb 16, 2024

Alex Sarama